By Júlia Hanesz

Introduction

AEGEE / European Students’ Forum is a non-governmental, politically independent, and non-profit student organization, which has around 13,000 members from close to 200 cities and almost 40 countries all over Europe. We strive for a democratic, diverse and borderless Europe, which is socially, economically and politically integrated and values the participation of young people in its construction and development. Our main mission is to strengthen mutual understanding among young Europeans and bring Europe closer by empowering them to take an active role in the society. For this reason, AEGEE aims to create a space for dialogue and learning opportunities for young people as well as act as their representative to decision makers.

Civic Education has become an important topic for our organization, while having a twofold approach and purpose. On the one hand, we aim to increase the civic competences of AEGEE members to enable them to become responsible citizens. On the other hand, we aim to put civic education on the political agenda at all levels. In 2008, AEGEE with other organizations lobbied for the introduction of the European Citizen’s Initiative (ECI) as the first transnational participatory democratic tool of the EU. We contributed to it by initiating a project called “Take Control – Ways to democracy in Europe”. Additionally, AEGEE took part in The ECI Campaign[1] together with many organisations such as Democracy International. Eight years later, AEGEE used the ECI to raise awareness on the topic of civic education by launching the “More than Education – Shaping Active and Responsible Citizens” European Citizens’ Initiative. The project has allowed us to develop our own civic competences and is, therefore, a great example of informal civic learning. Furthermore, the purpose of using the ECI tool has been to assess its strengths and the limitations as a tool for European citizens.

The following policy paper aims to achieve three things. First, the paper will highlight the importance of such a participatory democratic tool. Secondly, there will be a summary of the experience of young Europeans dealing with the ECI and lastly the paper will outline possible improvements for the ECI.

During the preparatory phase of the project we discovered some imperfections of the tool, therefore the development of this policy paper started in the initial stages of the ECI – More Than Education campaign.

The European Commission decided to address the issues related to the ECI and launched an official consultation process, which AEGEE also participated in. As we are primarily an organisation that focuses on youth, this policy paper highlights a youth perspective of the ECI. Moreover, we mention future activities that will form part of an overall strategy.

In the first section of this paper, some aspects of the wider social and political context are described, which highlight the relevance of the ECI and other forms of democratic innovation and citizen participation. This follows a short section characterising the most important details of organizing an ECI.

The relevance of direct participation in policy making, tools like referendums and citizens’ initiatives was examined in a survey among AEGEE members. Its results and implications are presented in the third section.

Following this, the story of the “More than Education – Shaping Active and Responsible Citizens” ECI organized by AEGEE members is detailed. Based on a questionnaire and interviews with members involved in the campaign, the main benefits of the tool are described and faced obstacles are identified in order to form recommendations for further improvement of the tool.

As a conclusion, the final position of AEGEE and recommendations towards the European Union and member states for the development of the ECI are stated in the last two sections.

01| Contextualisation

Today’s Europe is a multicultural society that is experiencing constant changes in terms of various socio-economic factors such as the intensive migratory flow to Europe from non-European countries as well as migratory flows between European countries. Furthermore, effects of the financial crisis of 2008 are still perceptible in many regions. Potential radicalisation among marginalized groups and the extremist movements have become a serious threat to Europe. The EU as an actor has an important role to play in tackling cross-border challenges. However, the EU itself is challenged by other issues (for instance by the Brexit) and this puts any further development of the EU into question.

Although 68% of the Europeans identify themselves as citizens of the EU, only 56% are optimistic about the future of the EU and less than half, 42%, think that their voices count on the EU level [1]. This shows that many Europeans are still not fully aware of the European civic identity. The democratic governance of some European countries was challenged through social movements like the 15M in Spain or the Syntagma protests in Greece, which strived for better political representation. These revealing issues or even crises of European democracy contributed to the rise of populist politics.

It seems that to face these challenges a great amount of flexibility is required and new political, economic and social solutions need to be found. Direct democracy can play an important role in these processes at the local, regional, national and even European level. However, we should be aware that direct democratic procedures have a long-term political cultural learning effect. People have to first acknowledge and practice such forms of decision-making, in particular with the help of public debates. During this process they are likely to develop a different and more cooperative view on their life, community and society they are living in [2].

If bearing in mind the literal meaning of the word ‘democracy’ as the rule of the people, ‘direct democracy’ aims to achieve the most direct translation of the people’s will into political decisions that is practically possible [3]. Therefore, direct democracy can be described as a political system, which enables citizens to decide for themselves whether to adopt or change laws [4]. Similarly, participatory democracy is founded on the action of citizens who can exercise some power directly and decide on issues affecting their lives, however, this does not involve voting on specific policies [5]. Most importantly both concepts allow citizens to participate directly in law and decision making processes in addition to the right to vote during elections for representatives in the parliament. Examples for direct democratic tools are referendums, recalls and examples for participatory democracy are citizens’ juries, town meetings or citizens’ assemblies and initiatives. The ECI is also considered to be a participatory democratic tool, since it enables the citizens from all member states to propose legislation to the European Commission, but it does not include voting on a given issue [6].

02| The European Citizens’ Initiative: One year, one million signatures

The ECI was introduced in 2012. Since then, more than 50 Citizens’ Committees have tried to launch their own initiatives and collect the million signatures required. Any ECI can be successful if at least one million signatures are collected. So far four of them succeeded. In the following section the procedure of the ‘One year, one million signatures’ is described.

The main body that manages the whole procedure of an ECI is the Citizens’ Committee, which consists of at least seven EU citizens coming from minimum of seven member states. They have to request the European Commission to register their initiative. The Commission has two months to decide whether the proposed initiative complies with the requirements set out in the Regulation[2] 211/2011 on the citizens’ initiative. In the meantime, the organisers have to set up a collection system and have it certified. If the aforementioned conditions are met, the Commission registers the ECI and the collection begins. One million EU citizens have to endorse the related idea of an ECI within one year from the date of registration for it to be successful. A minimum number of signatures[3] has to be met in at least seven member states – these countries being at the choice of the Committee. Organisers can collect the signatures, to be seen as statements of support, either online or on paper. Citizens who want to support an ECI must be eligible to vote in the European Parliament elections. After the one year period has expired, the organisers have to have the offline signatures verified by the national authorities of individual EU Member States. Only then can the ECI be submitted to the Commission.

The consequence of a successful ECI is the following: Representatives of the Commission have to meet with the organisers to allow them to further explain their objectives, the organisers can present their ECI at a public hearing in the European Parliament and finally, the Commission must respond to the ECI. The response needs to spell out arguments for the Commission’s decision whether to act on the ECI or not. The Commission is not obliged to take any positive action regarding the subject-matter of an ECI which, as will be further explained, presents one of the biggest issues in the current regulation.

The tool itself has provided a new platform on which Europeans can share their ideas and spread their beliefs. Yet, the before mentioned procedure is fraught with technical, administrative and legal difficulties that potentially inhibit the usefulness of the tool.

03| Relevance of the European Citizens’ Initiative in the eyes of young people

In order to find out AEGEE´s position on the matter of direct and participatory democracy in Europe, a survey was conducted among 124 AEGEE members from 20 countries.

More than 70% of the participants believe that it is important to be actively engaged in politics on local, national or international level. However, only 5,6% of the respondents thought that they can have a big influence on European politics in general. The majority believes that young people can have only a little or some influence.

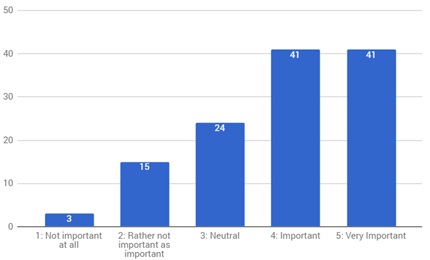

Having the possibility to participate directly in the legal decision making processes and to vote during elections was important for 75,6% of the participants. Only 12,1% of participants stated that it was not important at all or less important. Answers were similar when participants were asked about having this possibility at the European level. One of the participants highlighted two main reasons behind the importance of such a tool. For instance the control of the governance and the possibility to raise awareness about certain topics: “The only way a real democracy can work is by having the correct tools to control what politicians make. There should be a way to let our governments know that we do not agree with decisions they have made and to put on the table something that is being ignored.”

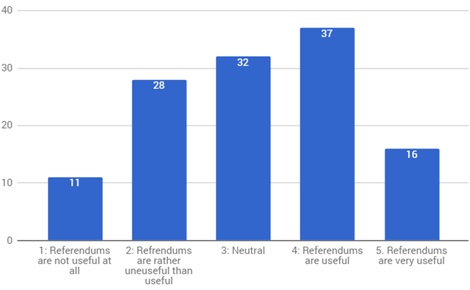

The results regarding the specific types of direct or participatory tools are more heterogeneous. 42,7% of the respondents thought that referendums are very or rather useful, 31,5%, stated that referendums are rather unuseful or not useful at all, and the rest 25,8% were neutral on this question. These results might be influenced by the recent use of referendums in some European countries with controversial outcomes, such as the Brexit or the referendum carried out in the Netherlands on the approval of the Association Agreement between the European Union and Ukraine.

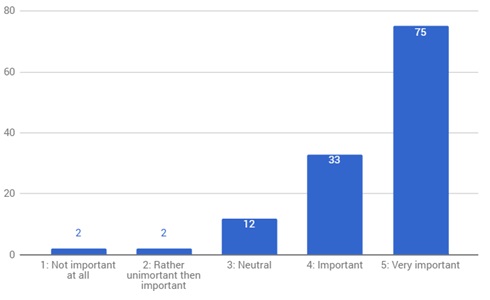

In contrast to referendums, the European Citizens’ Initiative was generally a more favoured tool among the participants of our survey. 86,83% of the respondents thought it is very or rather important than unimportant to have a right to start an ECI. “Although I’m not particularly in favour of a direct democracy, having a road into the political structures of the EU is very important. This can provide information about interests, wishes and red lines from the general population”- wrote one of the respondents. Others also identified that the ability to make your voice heard is a very important aspect of the ECI, which can also encourage people to be active citizens since they can change things through it. “The right to start an initiative is important because the motivation for many citizens to keep themselves informed about politics is directly linked to the degree of self-involvement that it requires.” In other words, an ECI can empower citizens since it also “…brings people together and motivates them to fight for their dreams/opinions/projects and not just cast a vote” and “…it also strengthens the feeling of having your voice matter and thus improves the general feeling about democracy in the EU.”

Although the above listed comments definitely support the ECI, many participants described their concerns about the actual impact of it: “The question, for me, however is the extent to which decision-makers actually change their opinions about it. I’m not certain of the answer to this question, but that does not mean that I don’t believe that the opportunity should be cherished and used maybe more often by Europeans citizens.” Similarly: “It is important, but it requires a huge effort and the result (examination by the Commission) does not have a particular impact.”

To summarise, young people find it relevant to have an opportunity to be involved directly or through participatory tools in the decision making process in the European Union. In contrast to referendums, which seem to be controversial among young Europeans, they favour the European Citizens’ Initiative, even though its impact is still questionable. We cannot conclude from this that more direct or participatory democracy itself would help young people to feel more involved and get more engaged in politics, but it could be one possible way to it. Improving the ECI tool itself, therefore, could be a significant step in fighting the challenges that Europe is facing.

04| Case study of the AEGEE ECI

The ECI “More than Education – Shaping Active and Responsible Citizens”[4] was registered on the 6th October 2016, with the following subject matter and main objectives:

Subject Matter:

A set of incentive measures, including support and monitoring, to develop citizenship education in curricula on all levels of formal education throughout Europe, aimed at shaping democratic citizens.

Main objectives:

A democratic society relies on the citizens’ participation, shared values and capability of critical thinking. The Commission should support member states in their responsibility to enable young people from all backgrounds to develop competencies for participating responsibly in society. To promote cohesion, action should be coordinated throughout the Union, by setting a long-term agenda, creating benchmarks, providing support to states, doing periodic evaluations and sharing best practice.

The preparation for this ECI started more than a year before registration by gathering a motivated team, later called the ECI task force. At the beginning, the team consisted of seven people, and later on other people joined to fulfil a certain task for a longer period or to participate in a specific project or event for a shorter time. Some people also left the task force throughout the preparatory phase, due to lack of time or losing motivation. It is important to highlight that all organizers participated in the campaign as volunteers, dedicating their time and effort to the project next to their studies and other duties. Results of the online survey conducted among 18 AEGEE members actively involved in the campaign showed that the main motivation behind joining the team was first of all the topic of civic education and secondly that they could get familiar and use the ECI. Even though for many of them this was the first time working with the tool, it brought a great opportunity to learn a lot and to educate AEGEE members about it. Therefore, when examining the development of the work and the results of this ECI, we should keep in mind the aspects of voluntary work and youth involvement.

During the preparatory phase, the task force consulted various experts such as professors, partners, civil servants and other ECI organizers. For instance Carsten Berg (the ECI Campaign) helped us to get a deeper understanding of the procedure and requirements of carrying out a ECI. Although, some of them emphasised that it is not worth the effort and the ECI should be improved in many aspects, we decided to continue keeping in mind that apart from the signature collection, our experience with the ECI could be a case study for further development of the tool. The consultations with many academics working on their masters and PhD theses on the ECI, showed us that there is a big interest in revising the tool.

On the 7th of July 2016 the ECI was registered by the European Commission for the first time. The announcement of it came as a surprise and because of technical difficulties with the online collection system, and because it seemed more feasible to start the campaign after summer, the AEGEE ECI had to be withdrawn.

The withdrawal from our side was met with concern from the European Commission’s side as the Commissioners had their meeting during which they decided to allow our Initiative around the same moment we sent our withdrawal statement. A phone call from the Commission asking us to reconsider our withdrawal suggested some political interest in our ECI, but the ECI was withdrawn nonetheless.

During the next three months a new website was created and the collection system hosted by the European Commission was set up by the task force and audited by the Luxembourgish authorities. For this audit, the organisers had to come up with a security policy, write a business impact assessment, risk assessment, and risk treatment plan, which was a challenging process in order to conform to high security standards. In this process, collaboration with the technical department of the European Commission went smoothly. However, it was difficult to understand what was happening on their side, as they take care of the development, installation and auditing of the software and servers.

Brainstorming for the campaign itself started as well. During summer events, some AEGEE members were introduced to the ECI and learned more about our own initiative. Finally, in October 2016 the ECI was registered for the second time and the signature collection could be started.

It was clear for the core team that for reaching one million people willing to sign the initiative a much bigger team was needed. Hence at the beginning we tried to focus on motivating AEGEE members to join the task force or organize a local signature collection and inviting other NGOs to set up coalition to do the ECI together. However, we met a very reluctant reaction from the civil society, emphasising that ECI is not worth the effort and it has no actual impact.

Motivating others can be difficult, especially if the goal of reaching the one million signatures seems impossible to them and it was not really the aim. The Activity Plan of the Civic Education Working Group of AEGEE, which started organizing the initiative stated: “Note that it is not feasible to collect a million signatures this year. However, we are going to start collecting signatures and involve the Network in that.” Considering the ECI as a great opportunity to promote the importance of civic education turned out to be a difficult way to encourage young people to join.

When asking members of the task force or other people involved in the campaign whether at the beginning they believed in reaching the needed number of signatures, out of 18 nearly 40% (7 people) believed in doing so. Other four people (22.2%) did not believe in collecting that many, and the rest was aware of some difficulties, but still hoped for success. On the contrary, 16 people would probably or for sure do it again.

Most of the respondents highlighted that they learned a lot, and that the ECI offered them the opportunity to raise their voice for an important topic for them, that they could be part of a big scale initiative. One of the team members said: “It made me aware of the fact that to voice something that needs to be changed it takes a lot of effort to get people to become aware of the topic. It takes a lot of communication, motivation and good will from a good team of people to be able to do something. It also made me believe that as young students you can voice something and it can be heard by the politicians.”

One of the aims of an ECI is to raise awareness about an important issue. This was fulfilled in the case of the “More than Education” ECI. Even though due to the lack of financial resources we were not able to run a traditional campaign, we were able to discuss civic education with many European students within AEGEE on various occasions, such as during ten network meetings reaching 400 members or at conferences of 1000 people, while all of them learned about ECI. The fourth edition of the project Europe on Track[5], thanks to ECI, was committed to raising awareness on this topic. The task force was present at the Yo!Fest in Maastricht, organized by the European Youth Forum and other external events presenting the ECI. In May 2017 we organized an event in the European Economic and Social Committee with the title: ‘Mind the gap – how to strengthen civic education for all throughout Europe’ and as an opening eventhosted in Budapest the Franck Biancheri Award Conference ‘Education for the present- Democracy for the future’ at the Central European University tackling the topic of civic education and its role in building a strong democracy.

The impact of the ECI could be seen in the launch of new cooperation with many external organizations working on the topic too. In other words, it became an important promotional and networking tool for AEGEE. We could spread our views about the need to improve civic education in Europe and because of the ECI many organizations reached out to us and this opened new doors. One great example is be the cooperation with the European Economic and Social Committee. Other than hosting our event, they supported our work by helping to translate materials for us, gave us an opportunity to be present and introduce our views during the ECI day organized by them and included us in the meeting of the ECI ad hoc group and further collaboration is planned as well.

While working on the ECI and during the signature collection events, the people involved identified some obstacles. Maybe the most crucial part was the lack of financial resources. The project was only run from the budget of AEGEE and some small online donations all in all less than 500 Euros. Other than that, the long and complex administrative process and setting up the IT infrastructure caused a delay in starting the campaign, what resulted in some people losing motivation and leaving the team, as well as a problematic planning for further steps.

When asking organizers of signature collections about their experience, they highlighted that the ECI in general was not known by citizens, so first they had to explain this concept in general before starting to explain our particular ECI. They also mentioned that both the online system and the paper forms are not user friendly and caused a lot of confusion during the campaign. Some obstacles were: filling the online form took a lot of time and the platform is not mobile friendly; in case of paper forms the required data differ in each country and the text itself is very small, signatories made a lot of mistakes during filling them in. Moreover, organizing a signature collection in a public place in some countries requires registration at an administrative body. However, in some cases even competent officers were not sure how to proceed with it.

Another aspect of the whole ECI process is the communication with the Commission, which was not ideal. Although, our ECI is not going to reach the one million signatures, and by that call the European Commission to put the improvement of civic education on their agenda, we were happy to see that many new initiatives on the topic of education are being prepared, such as the public consultation: Promoting social inclusion and shared values through formal and non-formal learning[6]. However, since we showed interest in the topic, and are willing to be actively included in the process, we were not informed about the ongoing work at the time of the registration.

Next to the ECI, an online petition[7] has started as well, so AEGEE members who come from non-EU countries can be included in the campaign too. However while this is useful to get support from the non-EU members, these statements of support do not count in the one million needed for a successful ECI.

05| Position of AEGEE-Europe

Today’s Europe is facing many challenges that cannot be adequately tackled by single countries only. AEGEE believes that a better integrated and borderless Europe is possible and that the creation of active, responsible and democratic citizens are key elements of it. These citizens should be able and willing to participate in the changes and to find solutions for current issues.

Having the opportunity to raise awareness and call policy makers to action regarding issues that concern each citizen on local, regional or national levels is important. But AEGEE also believes that it is important to engage with people from other countries. AEGEE advocates for democratic tools which will enable every European citizen to participate in the decision making processes at local, national, but also European levels.

The recent survey among the AEGEE members showed that many of them question the use of referendums; therefore the European Citizens’ Initiative represents a more relevant participatory tool for them.

Based on our experience, the ECI is a great opportunity to promote a topic and raise awareness about an issue that matters to citizens. Throughout the year of collecting signatures, thanks to the ECI we were able to reach out to many stakeholders dealing with civic education. However, our example also shows that collecting one million signatures for a youth organization relying on voluntary work is not possible yet. Reasons behind could be the lack of funding and a need for specific knowledge and experience but also the user friendliness and possible results of using the tool. For instance, some contacted NGO partners refused to cooperate with us, due to previous experiences with campaigns and they found the tool not worth to invest time and financial resources in it.

AEGEE is motivated to take an active role in shaping the future of Europe. Therefore, we call for a revision of the ECI to make it more accessible and usable for young Europeans. Fighting challenges faced by Europe nowadays is possible when every citizen feels responsible and is willing to bring their contribution to find solutions. Including more people – especially the youth – in policy making is a step towards in the development of a common European identity which is necessary for tackling common issues .

As we believe in the ECI is as an important tool, we

argue that it should be promoted and reshaped to a form, which truly enables citizens to raise their voices, influence policies and assist in creating a democratic Europe.

06| Recommendations for improving the European Citizens’ Initiative

AEGEE advocates for the following measures in order to make the ECI more accessible and usable for young Europeans.

6.1. Recommendations for the European Union

- The Commission should enter into dialogue/meet with organizers, not only at the end of the successful initiative but at the beginning of every registration in order to foster debate with citizens. The EC should be proactive in information the organizers on ongoing processes connected to the topic of their ECI and related issues.

- The Commission should provide the online platform for the online signature collection, so the technical side of the signature collection would not cause too much inconvenience to the citizens.

- Allow Citizens’ Committees to choose the starting date of the signature collection after the ECI has been registered, and within a certain period of time, in order to give them the opportunity to finish all the preparations and plan the campaign in detail. This would make it easier to apply for funds, since the organizers would be sure that the ECI is registered.

- Improve the platform where all ECIs are listed, by integrating information on European processes concerning the topics of the respective initiative.

- Offer financial support for Citizens’ Committees and/or financial advice on planning a campaign and applying for funds.

- Harmonize the minimum age of the signatories at 16 years of age in order to encourage young people to be active citizens from an early age onwards.

- Create a more user friendly platform for the online signature collection, which is easier to fill in, applicable for different websites and is accessible on mobile phones as well.

- Simplify and restructure the paper forms for offline signature collection, such as not having only three signatures per paper.

- It is of crucial importance that citizens of successful initiatives feel heard, taken seriously and are recognised in their efforts. Therefore, the hearing at the European Parliament should only be focused on them and other relevant experts and stakeholders that the Citizens’ Committee puts forward, even though this may not ensure a fully balanced debate with opposing viewpoints. But the Commission has other means at its disposal to ask for opinions from other stakeholders (such as a public consultation). Furthermore, the follow-up for successful ECIs should be improved: more details and fact-based answers from Commission should be given.

- Give a positive experience to unsuccessful ECI organizers: the Commission should address them personally in order to recognize their efforts and lay down the EU’s current actions related to the topic of the registered ECI. In order to recognise the efforts of organisers and to enhance the visibility of the ECI as a tool, the Commission should communicate via its own channels when ECIs reach certain numbers of signatures – milestones. Other than that, more information about the ECI should be given through (the channels of) national level authorities.

6.2. Recommendations for the Member States

- Harmonize the process of signature collection in the member states, such as the amount and type of personal data required to be filled in on the paper forms.

- Take an active role in informing citizens about the ECI and promoting it as a participatory democratic tool at the EU level.

- Create a user friendly environment for the ECI signature collection and offer country-specific advice for Citizens’ Committees, such as easily understandable and accessible guidelines.

References

[1] Standard Eurobarometer: Public opinion in the European Union, First results (87), pp. 21- 38.

[2] Dirk Berg-Schlosser (2007): Direct-democratic procedures as corrective mechanisms in consociational systems or for clientelistic structures—some brief remarks. In: Pállinger, Z., T., Kaufmann, B., Marxer, W., Schiller, T. (2007): Direct Democracy in Europe. GWV Fachverlage GmbH, Wiesbaden.

[3] Marxer, W. (2004): „Wir sind das Volk“ — Direkte Demokratie: Verfahren, Verbreitung, Wirkung. Beiträge Liechtenstein-Institut Nr. 24. Bendern.

[4] Lakoff, S. (1996): Democracy: History, Theory, Practice. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

[5] European Institute of Public Administration (EIPA), Maastricht (NL) Best, E., Augustyn, M., Lambermont, F. (2011): Direct and Participatory Democracy at Grassroots Level: Levers for forging EU citizenship and identity? European Institute of Public Administration (EIPA), Maastricht (NL).

[6] Altuna, A., Suárez, M. (Eds.) (2013). Rethinking Citizenship: New Voices in Euroculture. Groningen: Euroculture consortium.

Annex:

- Details of the survey: Relevance of the European Citizens’ Initiative as a direct democratic tool

- Conducted between 20th March and 3rd August 2017.

- Total number of respondents: 124. 119 AEGEE members + 5 non-AEGEE members

- Answers from 20 European countries: Belarus, Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, Estonia, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Turkey, Ukraine.

- Average respondent’s age: 23 years; median age: 23.

- Gender characteristics: 50,4% females, 48,4% males and 1,5% other or preferred not to share their gender.

Figure 1: How important is it in your view that citizens have the possibility to participate directly in law- and decision-making processes on EU level in addition to the right to vote during European Parliamentary elections?

Figure 2: Do you believe referendums are generally useful direct democratic tools (at either the national or the European level)?

Figure 3: Do you believe it is important for EU citizens to have the right to start a European Citizens’ Initiative?

Details of the survey about the ECI conducted among the task force and other AEGEE members involved in some project during the campaign

- Conducted between June 9th – August 8th 2017.

- Total number of respondents: 18.

- Answers from 10 European countries: Belgium, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia.

- Gender characteristics: 72,8% females, 27,8% males.

[1] More: http://www.citizens-initiative.eu/

[2] http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:02011R0211-20150728&from=EN

[3] http://ec.europa.eu/citizens-initiative/public/signatories

[4] More details: https://morethaneducation.eu/ https://ec.europa.eu/citizens-initiative/REQ-ECI-2016-000004/public/index.do

[5] The “Europe on Track” project was launched to capture young people’s vision and wishes for Europe in 2020. It is a youth-led project where six young ambassadors across Europe with InterRail passes for one month informing and interviewing young people about their vision of the Europe of tomorrow. In order to do so, they participate in local events bringing content and creating spaces for dialogue and discussion with a main focus that changes every year, achieving a bigger impact through a travel blog, videos and social media.

[6] More: https://ec.europa.eu/info/consultations/public-consultation-recommendation-promoting-social-inclusion-and-shared-values-through-formal-and-non-formal-learning_en

[7] More: https://www.openpetition.eu/petition/online/more-than-education-shaping-active-and-responsible-citizens